The first time I saw Maya (not her real name) huddled under blankets in a hospital bed in 2013, she had been to dozens of inpatient detox programs and residential treatment centers since she had begun using heroin two decades earlier. After every release, she returned to heroin use, usually within days.

Why didn’t treatment “stick”? Like many people with substance use disorders, Maya had absorbed the nihilism transmitted to her by health care providers and the programs that had failed her. Models of treatment had historically been infused with outdated and punitive notions of addiction as an issue of bad behavior and, too often, if a person wasn’t improving, it was deemed to be their fault. They’d be written off as in denial or worse — they had to “hit bottom” first.

The assumption was that patients were failing, not the antiquated systems in place for treating them. Cycling through these settings, Maya had come to believe there was no hope for her, and she would die using heroin.

During that hospital stay, my colleagues and I provided care that should not be considered radical, but is. It’s aligned with how people with other chronic illnesses, like diabetes or heart disease, are treated. We started with a medication that is effective at stopping addiction, coordinated linkage to ongoing chronic care management after Maya was discharged from the hospital, and treated her as a human being with a health problem.

This approach also communicated a simple message to Maya: You have a treatable disease for which you are not to blame and, with the help of a team of experts working in the same setting, you will recover.

With time, close partnership with her outpatient team, medication, and support, Maya is thriving and has been in full remission for more than a decade.

Her case is instructive as the U.S. reaches a pivotal moment to turn the tide of overdose fatalities. While the number of overdose deaths has soared to a staggering prediction of nearly 110,000 deaths each year, states are beginning to receive much-needed funding to address the crisis. As part of opioid settlements with drugmakers, distributors, and pharmacies, cities and towns have begun to receive what will be hundreds of millions of dollars for substance use disorder prevention, treatment, and recovery.

These settlements represent an unprecedented opportunity to transform addiction treatment in U.S. communities. Use of opioid settlement funds has been varied and not always transparent to date, ranging from investments in residential treatment, naloxone, and prevention programs in schools to law enforcement spending or filling old budget gaps. Given all that is known about effective interventions to improve recovery and prevent overdose, the top priority should be to fully integrate treatment for substance use disorder into health care systems.

Caring for addiction requires science-backed medical interventions coupled with personalized support that addresses a range of social drivers of health. This sort of holistic, integrated approach is standard for people receiving treatment for cancer, HIV, and other chronic conditions. Now it must become the standard for people with substance use disorders.

Imagine what it would look like if health care approached heart disease like it does addiction: A person who comes to an emergency department with a heart attack might be told they are to blame for their health condition because of lifestyle factors. If they were lucky, they might be given a list of cardiologists to call, and they might be sent home with a stern reminder not to have another heart attack. Even worse, they might be kicked out of the hospital, or fired by their cardiologist, if they had ongoing symptoms of their illness.

It is almost laughable to describe this absurd approach, yet it is continues to be a common experience for people with addiction. They are blamed, treated poorly, expected to navigate complex and siloed systems on their own, and are often terminated from care for ongoing substance use.

Now is the moment to turn away from this two-tiered approach, where addiction care bears little resemblance to the rest of medicine, and instead bring addiction treatment fully into health care systems.

This will require integrating addiction treatment into all primary care practices, as well as into every hospital and emergency department — essentially into every touchpoint across health care systems. This will allow people to access treatment without delay and with the same expectations around quality they would have for any other type of medical care.

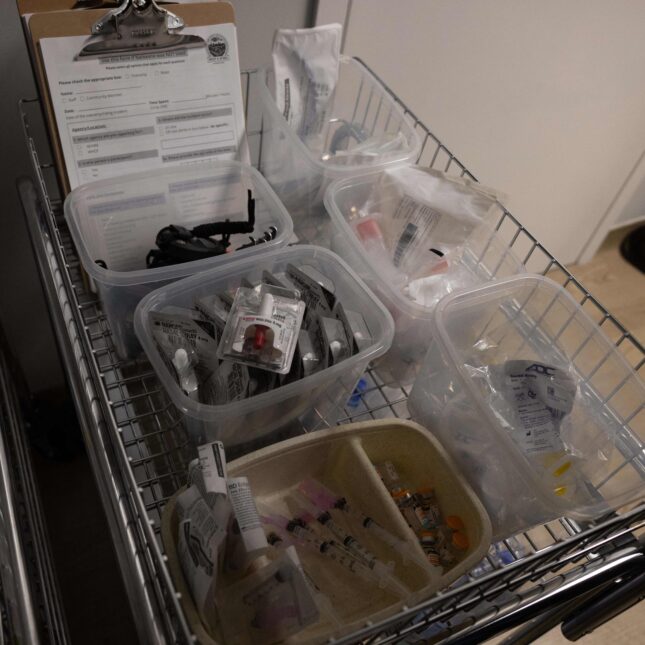

At Mass General Brigham, where I work, we are focusing on substance use disorder and equity in outcomes as a top clinical priority across the entire system. We are embedding addiction specialists, nurses, and peer recovery coaches — people who themselves have lived experience with recovery from addiction — into medical settings to support people on their journeys. We have opened four so-called bridge clinics across Massachusetts since 2016, which provide walk-in, easy-to-access, comprehensive substance use disorder care with multi-disciplinary teams of experts. And we are actively monitoring outcomes and improvements, all with a focus on eliminating inequities.

This integrated approach works. In 2014, Massachusetts General Hospital launched an inpatient addiction consult team focused on initiating treatment, including the use of lifesaving medications, and linking patients directly into ongoing care after individuals left the hospital. Providing these consultations was associated with a reduced 30-day hospital readmission rate among people with substance use disorders and improved outcomes. Integrating addiction treatment into the general hospital and emergency departments also increased the likelihood that patients continue on addiction treatment and reduced their addiction severity. Those receiving primary care in clinics with integrated addiction treatment are less likely to use emergency departments and hospitals.

Fully integrating addiction treatment into the health care system is a massive undertaking that will require time, resources, and a coordinated effort by health systems and local, state, and federal agencies. Perhaps most importantly it requires leaders who are unequivocal that addiction treatment is no longer something that a few providers or a few systems should opt into, but rather an expected and non-negotiable part of health care.

Leaders across the U.S. must make the most of this moment. Money from opioid settlements should be used to support full integration of addiction treatment into medical settings; expand welcoming, low-barrier programs like bridge clinics; develop the workforce through fellowship training programs; increase harm-reduction services, including overdose prevention centers; and provide robust support to address social drivers of health.

Now is the time to demonstrate what an ideal model for truly addressing addiction like a health condition could look like. The country needs to act on it.

Sarah E. Wakeman, an addiction medicine physician, serves as the senior medical director for substance use disorder at Mass General Brigham, medical director for the Mass General Hospital Program for Substance Use and Addiction Services, program director of the Mass General Addiction Medicine fellowship, and is an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

LETTER TO THE EDITOR

Have an opinion on this essay? Submit a letter to the editor here.

To submit a correction request, please visit our Contact Us page.

STAT encourages you to share your voice. We welcome your commentary, criticism, and expertise on our subscriber-only platform, STAT+ Connect