Where and when the Covid-19 pandemic began — in Wuhan, China in late 2019 — is well known. How it began is a matter of heated controversy. There are two competing hypotheses, one of which is hindering the process of scientific discovery and could hold back the development of vaccines and other antiviral agents in the U.S.

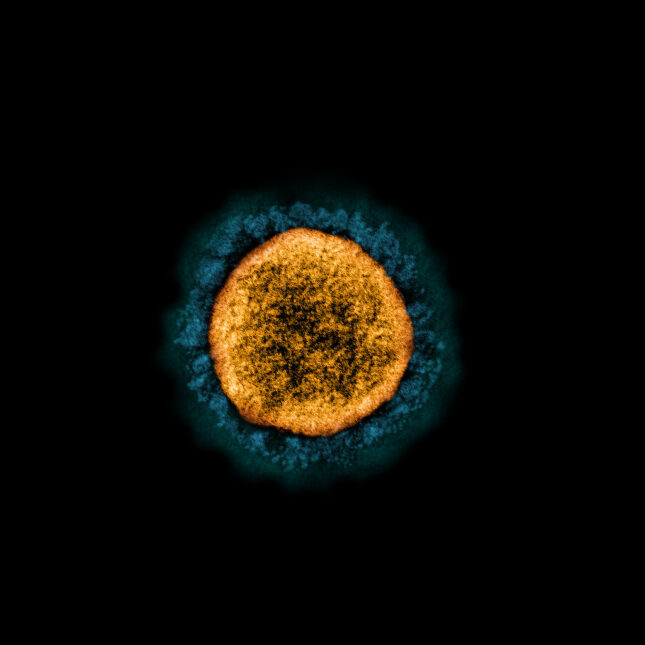

The zoonosis hypothesis proposes that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, was naturally transmitted from an animal to one or more humans in a so-called wet market in Wuhan selling fresh produce, meat, fish, and live animals. The lab leak hypothesis posits that the virus was modified (possibly through gain of function maneuvers), or even created, in the Wuhan Institute for Virology (WIV) and somehow escaped the laboratory.

Many politicians, pundits, and the general public now favor the lab leak idea. Most scientists, particularly virologists, do not. This schism threatens their legitimate and ultimately socially important work, as outlined in a peer-reviewed publication published on August 1 in the Journal of Virology that was written by 41 virologists. I am one of them.

The zoonosis hypothesis is solidly evidence based. Viruses often spill over from animals to humans, although usually as dead-end events without the sustained human-to-human transmission that sparks a pandemic. Wildlife coronaviruses have long been poised to infect humans. An estimated 66,000 people are infected with SARS coronaviruses each year due to human-bat contact, almost all resulting in asymptomatic infections with little or no further transmission.

That said, zoonotic transfer of three different coronaviruses (MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV-1, and SARS-CoV-2) from other animals to humans have resulted in epidemics or pandemics in the past 25 years. The 2002-2003 SARS-CoV-1 outbreak started in a Chinese wet market.

The influenza pandemic of 1918, which began from an animal-human cross-over, most likely from a pig in the U.S. heartland, killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide.

The illegal wildlife trade and wet markets are a $20 billion global industry with clear zoonosis risks. The more that humans and “exotic” animals mingle in close proximity, the greater the risk of viral transmission. There is the potential for a devastating pandemic with the H5N1 avian influenza virus entering birds and cattle and, sporadically, humans, in the U.S.

The lab leak hypothesis, in contrast, is essentially evidence-free: It relies on a chain of events that are unproven and highly speculative. A recent New York Times guest essay by Alina Chan, a molecular biologist at the Broad Institute of M.I.T. and Harvard, reiterates arguments first made in 2020 through 2022, but presents no new evidence.

The online and scientific literature support the zoonotic transfer hypothesis and/or counter the notion that a lab leak occurred.

Five of seven reports from the U.S. intelligence community favor the zoonotic origin of SARS-CoV-2, based on declassified scientific evidence and investigations. These five reports found no evidence that Wuhan Institute for Virology possessed SARS-CoV-2 or a closely related virus before the end of December 2019, and conclude that it is unlikely that SARS-CoV-2 was engineered.

Yet the lab leak hypothesis is now dominating discussions in the public square. It is being promoted by right-wing politicians and media celebrities, and even embraced by high-profile newspapers like The New York Times. The Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, has accepted the lab leak as established fact, dismissing the zoonosis hypothesis on dubious grounds. That matters, as the report outlines future government policies on relations with China.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, former director of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), testified in June 2024 before the House of Representatives subcommittee investigating the Covid-19 pandemic. He stated that people should keep an open mind on the competing hypotheses, pending definitive proof for one or the other. Despite taking a balanced position, Fauci was viciously abused, even told that he should be “prosecuted” and imprisoned for “crimes against humanity” because NIAID had sent grant funds for coronavirus research to the Wuhan Institute for Virology via an EcoHealth Alliance subcontract.

My concern, and that of many other virologists, is that the evidence-light lab leak hypothesis is damaging the virology research community at a time when it has an essential role to play in the face of pandemic threats. The attacks on Fauci are far from unique. Coronavirus virologists have been falsely accused of engineering SARS-CoV-2, allowing it to escape from a lab due to inadequate safety protocols, being participants in an international cover-up, and taking grants as bribes from NIAID for favoring the zoonosis hypothesis. There is mounting harassment, intimidation, threats and violence towards scientists that are particularly vile in the online space.

In a survey conducted by Science magazine, of 510 researchers publishing coronavirus research, 38% received insults, threats of violence, doxing (publicly providing personally identifiable information about an individual), and even face-to-face threats. A second survey of 1,281 scientists found that 51% had experienced at least one form of harassment, sometimes repeatedly for years.

As a result, scientists have withdrawn from social media platforms, rejected public speaking opportunities, and taken steps to protect themselves and their families. Some have even diverted their work to less controversial topics.

There are now long-term risks that fewer experts will help combat future pandemics; and that scientists will be less willing to communicate the findings of sophisticated, fast-moving research on global health topics. Pandemic preparation research has already been deferred, diverted or abandoned. Most worrisome is that the next generation of scientists has well-founded fears about becoming researchers on emerging viruses and pandemic science.

All virologists embrace the need for laboratory safety. None of them ignore the implications of the lab leak hypothesis — that there could be a future escape of a dangerous virus from a research laboratory. However, lab leak anxiety underpins proposals for policies that would unnecessarily restrict research on vaccines and antiviral agents in the U.S. The overarching concern here is that the lab leak narrative fuels mistrust in science and public health infrastructures. The increasingly virulent and widespread anti-science agenda damages individual scientists and their institutions, and hinders planning to counter future epidemics and pandemics.

Science is humanity’s best insurance policy against threats from nature, but it is a fragile enterprise that must be nourished and protected. Scientific organizations need to develop programs to counter anti-science and protect the research enterprise in the face of mounting hostility.

And the rhetoric being thrown at virologists must be toned down. Viruses are the real threats to humanity, not virologists.

John P. Moore, Ph.D., is a professor of microbiology and immunology at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City. This essay is adapted from a longer article written with 40 colleagues that was published in the Journal of Virology.

LETTER TO THE EDITOR

Have an opinion on this essay? Submit a letter to the editor here.

To submit a correction request, please visit our Contact Us page.

STAT encourages you to share your voice. We welcome your commentary, criticism, and expertise on our subscriber-only platform, STAT+ Connect