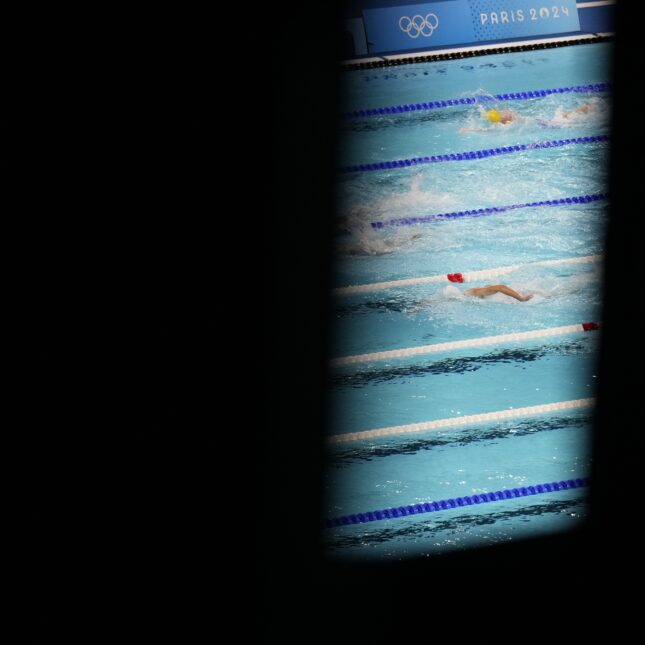

With Chinese swimmers getting 200 drug tests over 10 days ahead of the Paris Olympics, all eyes are on the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). Anti-doping is being politicized and some important questions are being asked with this Chinese fiasco. We believe an important question is this: Do performance-enhancing drugs actually work, or are they just placebos?

WADA bases its policies on a prohibited list of banned or performance-enhancing substances. To be placed on the list, a substance must meet at least two of three criteria: it is performance-enhancing; harmful to health; or a violation of the spirit of sport. Sanctions for using a substance on the list are severe, ranging from months of ineligibility and loss of rankings and earnings to lifetime bans from sport.

The justification for this draconian anti-doping policy it that it’s the only way to eliminate doping violations. But this policy is a failure for two reasons. First, there is very little evidence that the substances on the prohibited list are performance-enhancing or dangerous to health. Second, the very presence of the substance on the list may invoke a placebo effect regardless of its effectiveness.

A 2019 review examined the evidence for performance enhancement of the 23 classes of substances on the prohibited list and concluded there was no evidence of performance enhancement for the majority of classes of substances on the list: Either there were no studies available, or studies showed no positive effect. For the five classes of substances that did show performance enhancement in trained athletes, the evidence is based on 11 studies with 266 participants.

Why isn’t there more research? A big reason is that WADA explicitly discourages the use of banned substances in research related to performance enhancement (laid out in Article 19 of the World Anti-Doping Code) creating a scenario in which the true effects of these substances on athletic performance remain unknown.

Medicine has long known the powerful effect of placebos, which can translate into improved athletic performance. Strength athletes who believed they were taking steroids improved their maximal lifts minutes after being given a placebo pill they were told was a “fast-acting steroid.” Endurance runners who were given saline injections but told they were being given a substance similar to erythropoietin ran faster (erythropoietin increases red blood cell production which increases oxygen delivery to working muscles). Another group of trained runners ran faster when told they were being given a supplement that would enhance their performance, even if they were given a placebo. When these athletes were later told that they were being given a placebo but were actually given the supplement, their performance did not improve.

Countless studies of athletic performance show that athletes perform better when they believe they have been given caffeine, carbohydrates, calories, and other substances that are widely accepted as performance enhancing, even when they are given an inert placebo. The common factor is the belief that the substance is performance-enhancing.

Lance Armstrong became notorious for using various substances during his Tour de France victories, most notably erythropoietin (EPO). Recent research, however, challenges the belief that EPO provides a significant performance boost. In a rigorously conducted study, highly trained cyclists were administered EPO or a placebo. The culmination of the study was a race up Mont Ventoux in a test mimicking real-world cycling conditions. There was no discernable difference in performance between the two groups. This double-blinded, placebo-controlled study suggests that Armstrong’s dominance may not have been unfairly bolstered by performance-enhancing substances but rather by his inherent cycling prowess on any given race day, and perhaps by his belief that the substances he was taking provided him with an advantage.

Well-designed studies estimate that approximately 20% to 40% of elite athletes knowingly use banned substances for performance-enhancing purposes (including one study funded by, and subsequently blocked by sports authorities). If these banned substances were as dangerous as WADA would have us believe, elite athletes should be dropping like flies. But they aren’t. Former elite athletes live longer, healthier lives than their age-matched controls.

WADA has set up a system that severely punishes athletes for what, for all we know, are mere placebo effects, and then prevents research that could rectify the situation. We propose the following solutions:

Support and fund research. Encourage and fund comprehensive research into the effects of currently banned performance-enhancing drugs. This will provide a clearer understanding of their actual effects on athletes.

Health-centered regulation. Shift anti-doping regulations to prioritize the health and safety of athletes over the emphasis on performance enhancement. Emphasize evidence-based policies that mitigate health risks associated with substance use.

Medical supervision. Allow qualified health care providers to prescribe FDA-approved substances that may (or may not) enhance performance, with ongoing monitoring to manage health and prevent negative responses before they become catastrophic.

Current anti-doping measures are flawed and unjustly penalize athletes for believing in a myth rather than gaining any real unfair advantage.

Jo Morrison is a professor of kinesiology at Longwood University in Farmville, Va., where Eric Moore is a professor of philosophy.

LETTER TO THE EDITOR

Have an opinion on this essay? Submit a letter to the editor here.

To submit a correction request, please visit our Contact Us page.

STAT encourages you to share your voice. We welcome your commentary, criticism, and expertise on our subscriber-only platform, STAT+ Connect