As Covid-19 swept across the United States, schools were among the most highly affected public spaces. To prepare for a potential H5N1 avian influenza jump to humans, schools need to be preparing for the scenario now before a sustained transmission event occurs.

The response to Covid-19, which first appeared in the U.S. in early 2020, has been scrutinized by numerous case studies, after-action reports, and Congressional fact-finding hearings. Despite the federal government investing billions of dollars to improve public health infrastructure and efforts to streamline red tape through the new White House Office of Pandemic Preparedness and Response Policy, significant challenges remain. While these efforts suggest that the U.S. should be better prepared for the next pandemic, recent warnings from experts give pause for concern.

Robert Redfield, the former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, recently predicted that avian flu will cause a pandemic. Seth Berkley, the former CEO of GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance, derided the shocking ineptitude of the U.S. response to the avian flu outbreak among dairy cattle.

While these are individual opinions, they represent a growing sense of alarm among public health scientists that the H5N1 avian flu virus, which first infected humans in 1997, is developing characteristics that allow it to infect mammals more efficiently. With enough time and enough bad luck, the ability of this virus to infect and spread more efficiently between humans could be next.

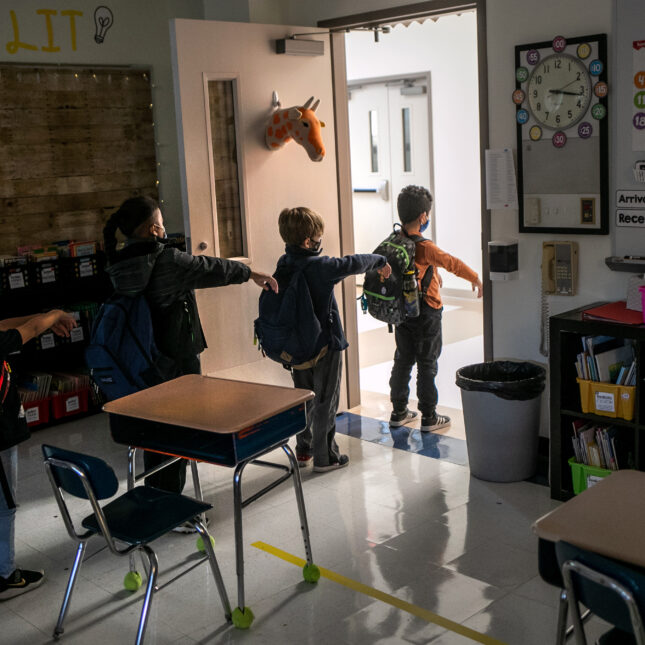

These warnings highlight a critical need for a more robust and adaptable plan, especially for protecting children and schools, severely affected by the faults in the Covid-19 pandemic response.

The problem is that the Pandemic Influenza Plan public health officials would likely turn to in the event H5N1 bird flu jumps to humans is the same as the playbook used for Covid-19. It didn’t work then for K-12 schools, and won’t work now.

Policymakers, public health experts, and education leaders need to consider what was learned during Covid-19 and make changes that reflect realities that exist on the ground today. These include:

In school settings, testing, contact tracing, masks, and isolation cannot be counted on to control the spread of an avian flu that has adapted to efficiently infect humans. Before Covid-19, these nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) were a cornerstone of pandemic response strategy. While such interventions can work for short periods of time in small settings, lack of consistent use and variability in operation make them unreliable over longer periods. It is also clear that views towards masks and other NPIs are influenced by political preferences, which further contribute to differing patterns of behavior and personal use.

Beyond political beliefs, however, reports have shown that parents routinely sent their children to school and daycare during Covid-19 because they had no other options for childcare. Students, as well as their parents and other family members, used masks infrequently, incorrectly, or not at all. Some chose not to test themselves for Covid-19 at home, while others tested too often. These decisions and their underlying motivations may be difficult for public health professionals to fully understand, but they must meet students, educators, and parents where they are. Instead of relying on nonpharmaceutical interventions, they should anticipate similar behavior patterns in the event of an avian flu pandemic and plan for it.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the lack of clear authority on decision-making related to school health policies led to inconsistent responses. Not much has changed since then. Many argued during the Covid-19 pandemic that if children’s needs had been prioritized by reopening schools ahead of reopening adult social settings, education losses could have been mitigated while also minimizing the impact of the social and emotional aspects of Covid-19-related isolation. Perhaps, but that’s not a debate that can be settled at this point.

Who takes responsibility for public health measures in the United States today emerges from a widely fragmented patchwork of incomplete administrative policies and political authorities that compete with fundamental ideals of free speech, individualism, and personal liberty. This realty, compounded by the fog of uncertainty in the early days of any viral outbreak, when nearly everything about an emerging infectious disease is up in the air, suggests a high likelihood of repeating the disjointed approach to Covid-19, with some jurisdictions opting to close schools to in-person instruction, others moving to hybrid learning, and others making no changes and remaining open.

Coordination processes between local school and public health leaders remain highly variable across the country. If an H5N1 pandemic does emerge, there will be calls for social distancing and school closures to protect students and teachers, just as was seen in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic. The challenges may even be the same: It will take time before it is known how efficiently the virus is spreading, what the case and case fatality rates are, and whether — and how long — schools should remain closed. But this time it will be happening among a public more skeptical of school closures and rightfully expecting far better coordination between health and education officials.

While some districts instituted public health department and school data-sharing practices during the Covid-19 pandemic, these structures have not been institutionalized or scaled reproducibly across the country. Systems like these, which help public health officials understand how disease is spreading within schools and the community, are critical for understanding disease transmission patterns and whether tools like closing schools are necessary. This period right now, between health security events, offers school leaders a chance to pressure test health data sharing systems and online education platforms; perform scenario exercises that test attendance, supply chain, and meal service delivery modeling; and practice online instruction, all of which are critical to improve upon the failures from the collective experience of Covid-19.

Preparing schools for the next pandemic

In light of this growing potential for a global pandemic from a virus with a high mortality rate, and in the face of unreliable nonpharmaceutical interventions and ineffective local public health infrastructure, what should be done to protect children and schools?

Vaccination is one answer, but given the significant disagreement in society about this measure, vaccine mandates are not a realistic option. In its place, getting schools ready for a pandemic will require steps from both the education community and federal health leaders.

Step 1 involves urgently and intentionally addressing the gaps between theoretical and practical emergency pandemic response planning that exists in schools. This includes approaching these policies with greater nuance and deeper understanding. School disaster-response plans frequently address other natural and manmade emergencies with greater specificity, but leave infectious disease outbreaks with vague and nonspecific action steps. District superintendents and school principals should use the interpandemic period to take a comprehensive accounting of what changes were instituted during the response to Covid-19, adapt best practices to local contexts, and codify these policies to respond to the challenges laid out above.

Step 2 in preparing schools for a pandemic requires action by both the education community and federal health leaders to:

- Test health data-sharing systems and policies. School districts should establish and test robust, real-time absenteeism data-sharing practices with local health authorities. This should include the pre-approval of memoranda of understanding that can facilitate this data sharing while also protecting personal health information.

- Conduct tabletop exercises. As with leaders responsible for other critical infrastructure, education leaders should conduct tabletop scenario exercises with local public health leaders to simulate various disease outbreak, vaccination, and treatment scenarios, test critical supply chains, evaluate online education delivery, and improve overall response strategies.

- Strengthen communication plans. Effective communication between the scientific and education communities was a critical failure during the Covid-19 pandemic. School leaders should develop clear communication plans to keep parents, students, staff, and local governmental leaders, including public health officials, informed about health measures and changes in school operations. These plans should be communicated regularly at school assemblies, parent-teacher conferences, and included with report cards and other mailings to facilitate stakeholder engagement.

Step 3 is out of the hands of those in the education community, but is essential: Federal health officials need to accelerate development of both cell-based and mRNA vaccines for pediatric populations as well as for adults. The federal government has made the decision to fill and finish 4.8 million doses of a cell-based vaccine to combat avian influenza, and just announced funding for a Phase 3 trial and acquisition vehicle of an mRNA based vaccine. However, it is unclear whether these trials and purchases include doses for children and adolescents that can be safety tested and made available as quickly as possible.

In the event of an H5N1 bird flu pandemic, recreating the Covid-19 experience, in which adult vaccines were approved six months ahead of the pediatric doses, is a recipe for disaster. If the worst comes to pass and this virus makes an efficient jump to humans, vaccines for both adults and children will need to be ready on day one.

These are not easy actions to focus on when school budgets are shrinking and leaders are still focused on education recovery after Covid-19. But by taking these steps during this critical interpandemic period, schools will be better prepared for future health security emergencies which will mitigate disruptions to education and ensure a more resilient response.

Mario Ramirez, M.D., is an emergency medicine physician, current managing director at Opportunity Labs, and former Acting Director for Pandemic and Emerging Threats in the Office of Global Affairs at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Opportunity Labs is a national nonprofit working at the intersection of public health and K-12 education to help improve outcomes for children.

LETTER TO THE EDITOR

Have an opinion on this essay? Submit a letter to the editor here.

To submit a correction request, please visit our Contact Us page.

STAT encourages you to share your voice. We welcome your commentary, criticism, and expertise on our subscriber-only platform, STAT+ Connect