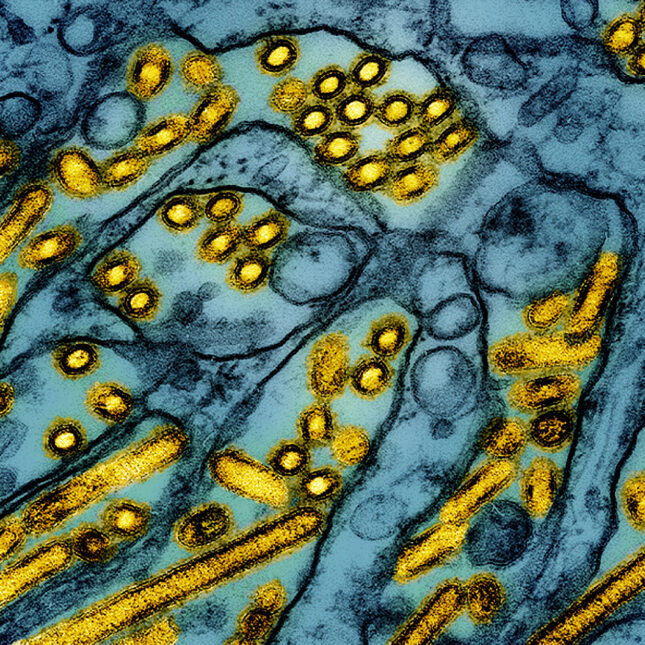

As the H5N1 bird flu outbreak in dairy cows enters its fourth month, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is taking steps to ramp up the nation’s capacity to test for the virus in people.

In a call with reporters Tuesday, Nirav Shah, the CDC’s principal deputy director, emphasized that the risk to the general public remains low at this time. But given that the virus is showing no signs of slowing its push deeper into the U.S. cattle population — threatening to create lasting risks to dairy workers and giving it more chances to evolve in ways that make it better at spreading to and among humans — the agency is looking to increase the number and types of tests that can effectively detect H5N1 infections in people.

“We need to stay prepared for the possibility of an expansion of the H5N1 outbreak in humans,” Shah said.

Currently, the CDC’s bird flu test is the only one the Food and Drug Administration has authorized for use. Shah said the agency has distributed 750,000 of these tests to local public public health labs, and is expecting 1.2 million more to come online in the next two to three months.

But should the virus begin to spread easily among humans, testing needs may quickly outpace existing public health laboratory capacity. Which is why the CDC is also working with commercial labs to build additional tests. So far, the agency has given eight companies licenses for its tests, Shah said. Three additional licenses are pending and another four companies are in the process of applying for licenses.

The effort appears to be aimed at avoiding mistakes the federal government made in the early months of the Covid-19 pandemic, when testing failures — including a slow recruitment of commercial labs to the response — allowed the coronavirus to spread undetected.

The CDC and local health departments have tried to boost bird flu testing among farmworkers — including with financial incentives — but uptake has been slow. Since the outbreak was recognized in March, the U.S. has tested only 53 people for novel influenza strains, which would include H5N1, according to the CDC’s latest figures. Three people — one farmworker in Texas and two in Michigan — tested positive for the virus. Two experienced only minor symptoms, namely conjunctivitis, or pink eye. The third had more traditional flu-like respiratory symptoms, and all three recovered.

Many dairy workers are immigrants, who live in rural areas with little access to transportation and no sick leave, making it difficult to travel to health care providers for testing and treatment. While acknowledging these challenges, public health experts have criticized the lack of testing, which is making it difficult to know how many farmworkers have been infected. Insufficient surveillance could also mean public health agencies might miss signs of human-to-human spread of the H5N1 virus.

The labs granted CDC licenses will still have to have their versions of the CDC test cleared for use by the FDA before they can be rolled out. Part of that approval process is proving the tests work. And to conduct such validation studies, labs and diagnostics manufacturers need control materials — samples that carry enough of the virus that they will light up a test as positive. That gets more complicated with a flu virus like H5N1, which is highly pathogenic, and therefore requires additional biosafety controls to work with in a lab.

To streamline the test validation process, the CDC is working to develop a non-virulent form of the control material, which it plans to provide to diagnostics manufacturers and commercial testing labs, although Shah did not provide a timeline for when they would become available.

The agency is also entreating the diagnostics industry to develop additional kinds of H5N1 tests, to broaden the nation’s portfolio of viral detection capabilities. On June 10, CDC put out a call for innovative testing solutions that can be easily ramped up to handle at least a million samples by the end of this year. The agency is now reviewing those applications, Shah said, with a goal of awarding funding to the winning companies by the end of August.

On Tuesday, the federal government also announced plans to support the development of messenger RNA-based pandemic influenza vaccines, including those that target H5 and H7 avian influenza viruses. BARDA, the Biomedical Advanced Research Development Authority, awarded Moderna $176 million to accelerate clinical testing of its pandemic vaccines, which are expected to enter a Phase 3 trial sometime next year. The U.S. government already has vaccine contracts and stockpiles of H5 vaccines made using other platforms by other manufacturers, including CSL Seqirus and Sanofi.

Dawn O’Connell, assistant secretary for preparedness and response at the Department for Health and Human Services, said at the press briefing that nearly 5 million doses of H5 vaccine stored in bulk in the National Pre-Pandemic Influenza Vaccine Stockpile are now in the process of being put into vials, in case it’s needed. “Our expectation is that those first doses will begin coming off the line in the middle of this month,” O’Connell said. “We remain extraordinarily watchful regarding the situation that we’re all tracking regarding dairy cows and working very closely with our other public health partners trying to understand if and when we should move these vaccines from the lines and out into deployment.”

As of Tuesday, the Department of Agriculture has reported infections in 137 dairy herds in 12 states. That tally doesn’t include four additional infected herds reported by state authorities this week, including one each in Iowa and Minnesota and two in Colorado. With 27 outbreaks in Colorado — most of which have occurred in the last month — that state has now seen nearly one-quarter of its dairy herds infected with the virus.

To submit a correction request, please visit our Contact Us page.

STAT encourages you to share your voice. We welcome your commentary, criticism, and expertise on our subscriber-only platform, STAT+ Connect